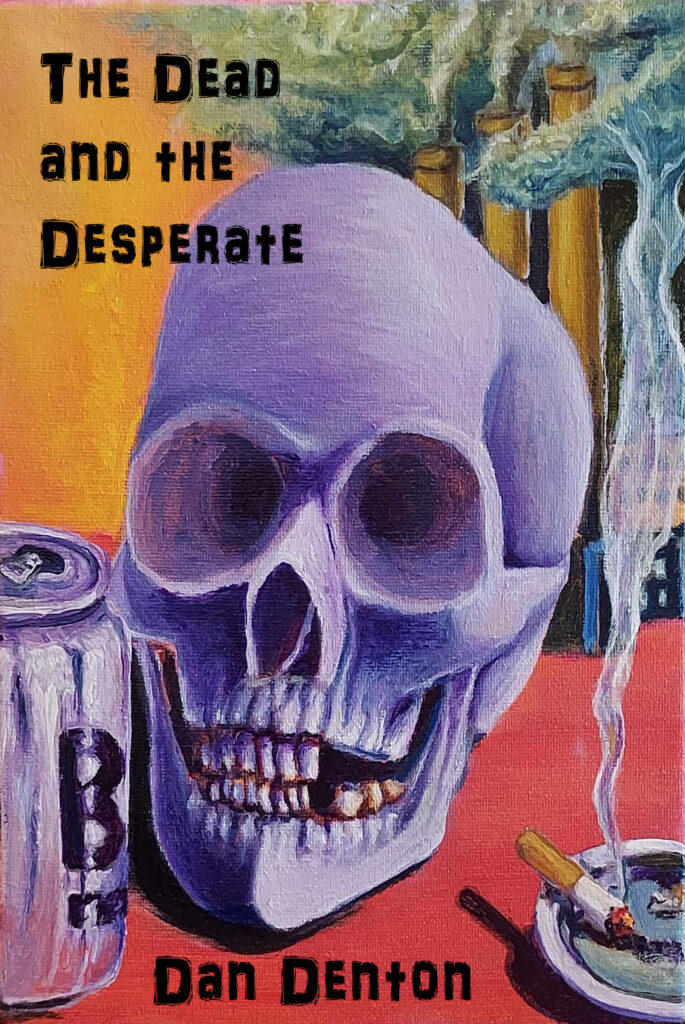

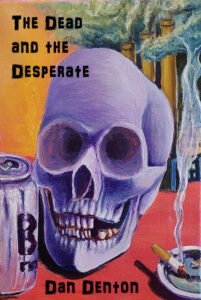

The Dead and the Desperate

The Dead and the Desperate

By Dan Denton

Genre: Literary Fiction

Reviewed by Maxwell Gillmer, Independent Book Review

Beautifully written and utterly raw—a

harrowing look at the life of an American

factory worker

There is no title more fitting for Dan Denton’s third book than The Dead and the Desperate. The story is borne of these two elements: those dead of this world, (one figure) and those desperate who are stuck living (the other). However, these two paradigmatic figures are by no means a simplistic demonstration of a forthcoming plot; they rather incite an explosion of realism and humanity that examines the struggles that come with American late-stage capitalism. These figures operate much like shepherds, always a step ahead of the sentence, casting a shadow over the world of the narrative.

The Dead and the Desperate calls into question the function of the novel’s title and how it, in an abrupt vision, can initiate a story, much like a portal into another space and time coerced by capitalism and plagued with struggling. Though, what summary is there to give for a story in which a person struggles in their entirety? What plot is there of a beginning, a middle, and an end when the story existed before the first page

and continues beyond the last? What Denton offers is the life of the novel’s unnamed narrator—a factory worker. It doesn’t matter what kind of worker, it doesn’t matter what kind of factory; in this universe, reflective of our own, people appear trapped.

The story begins with Ohio, a place to which the narrator said he would never move again after leaving behind lives of divorce, rehab, jail, and homelessness, and yet somehow, he finds himself sucked back after getting a woman pregnant. He does what he is told is right: marry her, get a job at a local factory, support the kid, have another. But for the narrator, living day to day by way of onerous “factory math” where a 12-

hour shift feels like 18 hours of labor, what is deemed “right” never seems to pay off. The narrator falls back into a cycle of misery. This marriage looks like it’s headed toward divorce; those misdemeanor charges are piling up; he can’t pay his utility bills and his rent is coming up next, and on top of all of this, he has to work another 12-hour shift at the factory. No matter what he does, he can’t seem to escape. As a result,

he’s drained of life itself. He seems stuck on a track ending at the bar after his shift ends, throwing back dollar beers and two-dollar shots that feed a fire in his body. He returns home drunken and enflamed and fights with his wife. Slowly the narrator finds his life unwoven, thread by thread.

The Dead and the Desperate is a heartbreaking story of the tragedies of life defined by late-stage capitalism filled with potent imagery and written with tear-jerkingly beautiful prose. The narrator admits he is the ideal American factory worker, saying “I’m a college dropout with a high school diploma. I don’t have any skilled trades licenses, or technical training. I’m smart, and don’t mind working hard hours and long hours. I’ve worked in almost all the kinds of plants and factories you’ll find in the Midwest, and I’ve ran almost all the kinds of machines they have in those factories.” He can do anything, and he will do anything because he has to. Under American capitalism, it doesn’t matter who you are or where you are; all that matters is what you are. And he is defined.

But what the book’s specters, the dead and the desperate, see, the narrator cannot. He grasps for rationales to understand why his life and the lives around him are crumbling under the weight of long hours, heavy machinery, drugs, and alcohol. He intermittently traces American histories of mental health care, wage gaps, divorce rates, and alcoholism and drug use in search of an explanation. The book is a flurry of topical substance that the narrator uses as tools to analyze how and why life around him could be so agonizing, but The Dead and the Desperate is not a polemic in its form.

Susan Sontag offers a distinction of narrative argument as either proof or analysis in her essay “Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie.” Sontag defines proof as a narrative in which something happens in its entirety—a demonstration of events as a result of given precipitants—while analysis is a narrative that seeks “further angles of understanding, new realms of causality,” and is, as a result, “always incomplete” to explain how and

why. Sontag argues that art trends toward proof rather than analysis, but Denton’s The Dead and the Desperate reflects the existence of both within a story of an individual and one’s tendency to seek a greater truth.

The novel as an argumentative tool of analysis, especially when dealing with an intimate relationship of a first-person narrator, runs the risk of pathologizing inexcusable behavior (racism, homophobia, sexism, etc.). When behaviors are depicted as pathologies, the perpetrators of these behaviors may place the onus of

their actions onto the source of the affliction rather than themselves. What makes The Dead and the Desperate powerful is that its offered analysis extends beyond the system that governs the individual and includes the individual within self-governance.

The book does not seek to absolve him of his sins and neither does he. People throughout the novel call the narrator a scum bag, and he never denies it. But the entire scope of the characters and the universe in which they operate must be known in its entirety to demonstrate a story beyond one single character and offer humanity to those who even do him harm just as he does harm to others.

This process of broken analysis is constant throughout the book. Just as the narrator is about to complete a singular path of analysis that would remove his culpability and place blame on the system of capitalism, the narrator steps back. In one instance, he admits, “I have done things in life that have hurt others, and I have had hurts done to me. None of that serves as an excuse.” Rather than an excuse, the narrator implicates himself, demonstrating that he can simultaneously be a person with an unchecked bipolar diagnosis and an addiction to drugs and alcohol with no support system, while also including him as a part of this world that oppresses other people, namely women in this story.

The Dead and the Desperate is a challenge—it is a hypermasculine narrative looking intimately into the psyche of a character who abuses women both emotionally and physically. However, in its refusal to take the final step in pathologizing the narrator’s behavior as something outside of his control, it shifts to a narrative of proof that stands on its own. There is no justification in this shift because justification would be beside the point. It offers a look into the mind of someone who has been scarred—someone who does scar.

Denton tempers the urge to fall too far into portraying his characters as strictly victims by redirecting the narrator’s voice away from melodrama, saving the narrative from becoming self-pitying in its depiction of hardships, and replaces it with a detached narrative style. The style permits the reader to see but never truly hear what is going on, such as when fighting with his wife. In these instances, spoken words are given

with little direction on how the reader should feel. But is this formal distance a prescription of impersonality or a degree of intimacy? It is a trick that encourages empathy—the reader is only given so much, and not because the narrator is withholding, but because the narrator is unable to give. The reader must cast aside any predilections and instead observe the situation as an invited participant.

The reader doesn’t have to know entirely why the narrator acts in the way that he does because the narrator cannot. Denton arranges an observation of what the narrator, much like the other characters in the book, is left with: moments of pain and moments at which the pain can be assuaged. The narrative is a reflection of this human tendency to reach for analysis, though ultimately being left in a position of observance. The novel is humble in this sense that it does not try to complete the interminable search however interminable in its struggle.

But there is a profound exhaustion that courses throughout this book at the expense of this search and struggle. The mind can just barely comprehend the suffering it endures, and when faced with the need to escape, the people of the story turn to the carnal: sex and drugs. On a sex- and drug-fueled bender, the narrator writes, “It felt good to not feel anything. To not feel the factory aches in my knees and shoulders

and hands. To not think about dead kids and kids you haven’t seen. To not think about how you’re gonna make the rent next week, or whether you were gonna go to jail at next month’s court date.” The narrator in searching high and low for moments of feeling tries his hand at different approaches to finding peace in his life, however fleeting, as if life, itself, is a partner whom he must understand.

The Dead and The Desperate in this sense is something like a Danse Macabre, twofold in its imagery. The first being that image of the title—the specters of the dead and the desperate moving together—and the second being the narrator and his life.

When one seeks to dance with a partner, one must know that partner’s footing. The specters of the dead and the desperate dance with each other just steps before the narrator. The desperate appears to struggle with its partner, death, and the narrator observes. He watches what the others do, attempting to trace why—what of this cruel world allows children to die and leaves so many others in agony—but while turned, he finds himself placed in the throes of his own missteps in the dance with his life.

The title, in this sense, does not just offer elements that act as the catalyst, but instead, it pulls the characters through in a duality of being: death and life; struggling and surviving. Only when the narrator can turn back and face his life as it stands before him can he find his footing.

The Dead and the Desperate is a massive undertaking of American life and struggle. Denton doesn’t bite off more than he can chew. He nibbles. He gives just as little as the narrator is given. Life, after all, is not all-encompassing, and only a small few are given it in its entirety. The Dead and the Desperate is one in one thousand. It observes the destruction of the American Dream and the American Life, and it offers a look into

an individual’s tendency to make sense of it all.

The Dead and the Desperate is available for pre-order at magicaljeep.com and will soon be available online wherever books are sold.