Somewhere in the light filled mist of San Francisco teetering at the edge of the world wandering through the ghostly landscape of the pandemic drinking in parks and peeking out cheap chipped windows are the fiery eyes of William Taylor Jr. This candid glimpse into a poet’s life is where, “the universe is dumb and vast with our failures and the loneliness of it is the only perfect thing,” and “the gossip parlors of the void” ring in the ears after midnight. I too “like books and poems, films and paintings that tell stories of sad lovers in old rooms existing as if in some abandoned dream.” I too live that way. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is “full of tourists ordering complicated drinks.”

Somewhere in the light filled mist of San Francisco teetering at the edge of the world wandering through the ghostly landscape of the pandemic drinking in parks and peeking out cheap chipped windows are the fiery eyes of William Taylor Jr. This candid glimpse into a poet’s life is where, “the universe is dumb and vast with our failures and the loneliness of it is the only perfect thing,” and “the gossip parlors of the void” ring in the ears after midnight. I too “like books and poems, films and paintings that tell stories of sad lovers in old rooms existing as if in some abandoned dream.” I too live that way. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is “full of tourists ordering complicated drinks.”

Somehow a poet is more sensitive to the apocalyptic Zeitgeist, but more prepared for it. The poet has long since lived with that hellish hue on his shoulder pressed against the perspective of cosmic time. Eternity at once burns us like an insect under an unseeing magnifying glass as well as sets us free. It’s an answer echoing from the abyss, it’s “listening to the broken music at the heart of the world,” it’s “our lives just an awkward silence beneath a temporary sun, stillborn moments caught in the air like mist,” it’s everyday life, it’s a likely story you can’t believe, it’s A Room Above A Convenience Store.

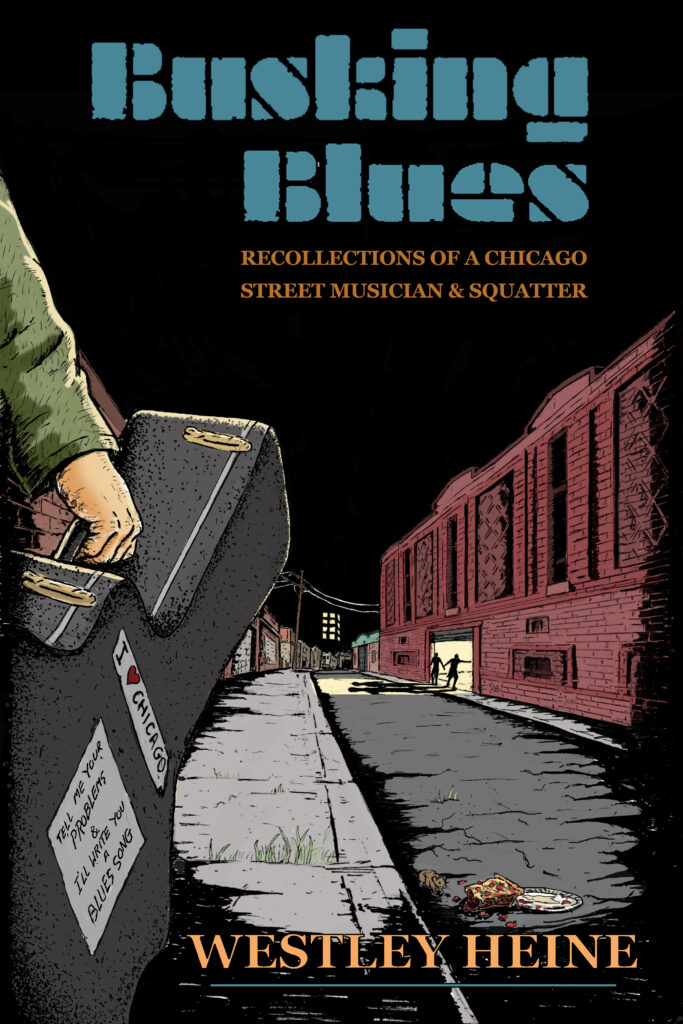

—Westley Heine, author of Street Corner Spirits and Busking Blues: Recollections of a Chicago Street Musician and Squatter