“… he clarified his intention, which was “beat” as beatific, as in “dark night of the soul,” or “cloud of unknowing,” the necessary beatness of darkness that proceeds opening up to light, egolessness, giving room for religious illumination.”—Allen Ginsberg

In some ways, Gregory Corso represented a darkness within a darkness: a beat within the Beat. His place within the inner circle of the Beat Generation (those he called the “Beat Daddies”: Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg, and himself) was undeniable, but he’s frequently left out of the movement’s critical considerations. Who can say why? Ultimately, such critical summations and anthologies often operate as autopsies for literary movements: attempts to articulate some kind of unity or clarity out of the naturally disparate materials of a generation, a life, an oeuvre.

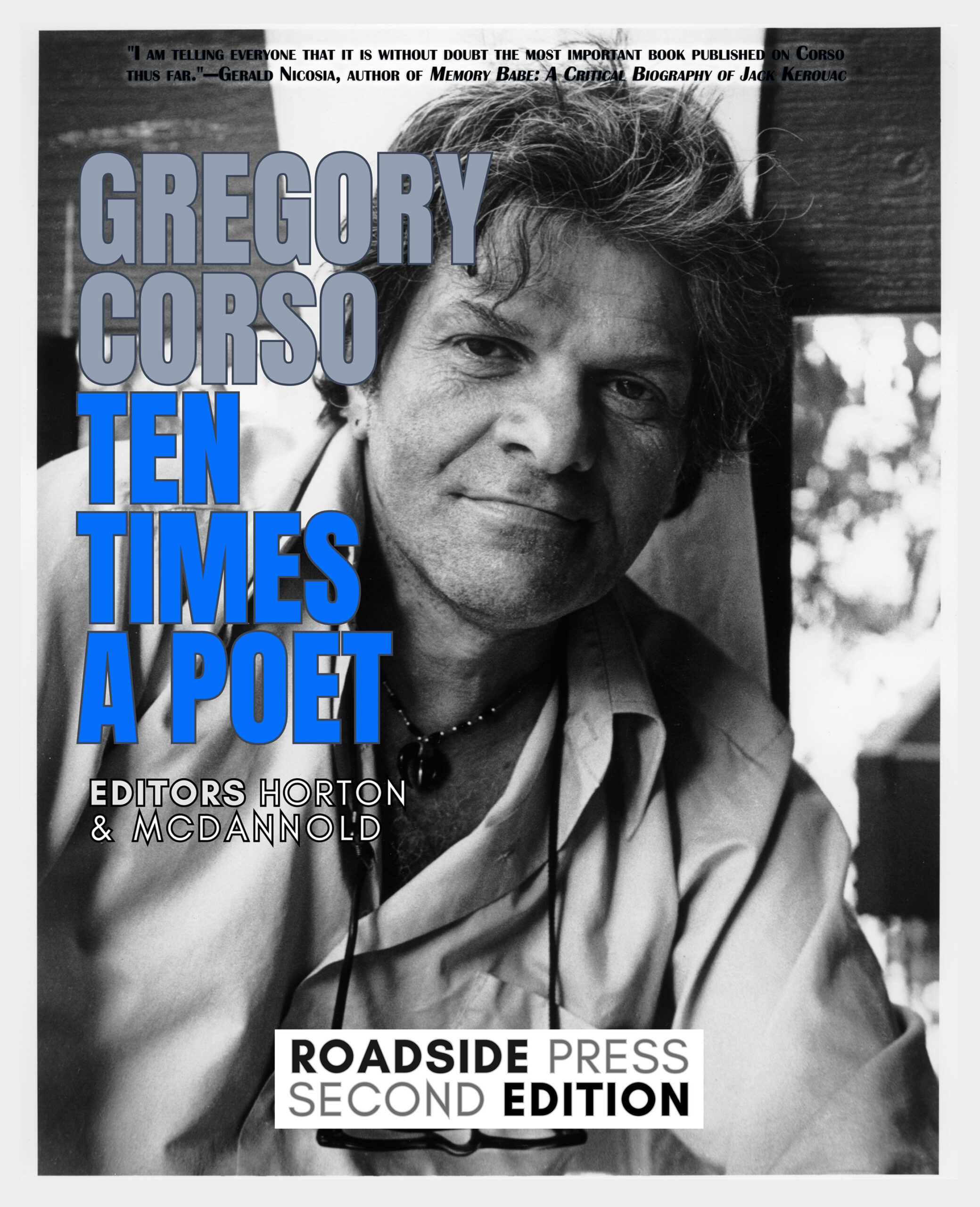

Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet, a new elegiac collection of essays and poetry released by Roadside Press, is at its best when it skirts any attempt to make Corso or his generation sensible. At its worst, it succumbs to a desire to elevate Corso into posthumous order or sensibility.

The collection’s opening essays are perhaps the most egregious examples of the latter, run through with causal platitudes (“We can only grasp Corso’s success by understanding the trauma of his childhood” [11]) and unapologetic psychoanalytic assumptions (“His memory of childhood became synonymous with his memory of defying authority” [18]). It may be that such examples are merely indicative of the biographical fallacy within literary criticism—that the narrative order afforded a dead poet cannot ever map cleanly onto the fundamentally immanent and elusive nature of their work.

This fallacy is particularly egregious in context given Corso’s own living desire to upend logic and explication. Consider the following anecdote from Kirby Olson’s “An Iconoclast at Naropa,” also in the collection:

Someone suggested we walk to a bar about two blocks away. At the bar, [Corso] began to talk about geometry in poetry. He discussed the poem by Jacques Prevert in which the disciples’ plates at the Last Supper are said to have been behind their heads. Corso began to talk about circles, and mentioned a line by Hans Arp. ‘A circle amuses itself.’ He then moved on to a discussion of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem about a moat with shadows that are infinitely deep. He said that nothing finite can be infinite. He looked at me then, and said, ‘You’re going to ask WHY? Aren’t you? WHY? WHY? WHY?’ (119)

The self-amusing circle and the infinite shadows are effective metaphors for the immense risk tacitly present in any posthumous literary-critical effort. The finitude Corso cites may be read as the finitude of life itself, out from which the poet (and his critic) stretches hopelessly toward an imagined infinity. Biographical and psychoanalytic causality are the crudest forms of the circle—uncritical and artless invocations of infinity and totality—and therefore the points at which this collection falls short. Gerald Nicosia said it best in his “Poem for Gregory Corso’s Ashes in the English Cemetery in Rome”:

That only the truly

And forever dead

Would dream of

Digging up

Someone who is still alive

Underground.

Luckily, these engagements are few and far between. Disinterested historicity soon gives way to something more intimate.

What ultimately makes this collection special are the personal narratives from those who knew Corso and have no interest in making sense of his life or his work. Each of these more effective essays offer a little window into a moment in the poet’s life: his charged visits to heroin dealers, his comical and erudite poetry readings, his world travels, his impromptu lectures on classical art around the dinner table, his insistence on reading the works of young poets… these fragments of a life steeped in art, tragedy, and a tenuous balance of street-level empathy and bon vivant elitism feel the most true to the man himself. More importantly, they feel true to the fragments and paradoxes of his work.

Robert Yarra’s “Gregory Gave Me the World” is a fine example of this even finer mode of remembrance. Perhaps it has something to do with Yarra’s somewhat outsider status within the world of poetry: when he first met Corso, Yarra was an immigration lawyer. Yarra quickly became a kind of patron to Corso, learning to “take the horrible with the sublime”:

I had dough and never turned him down for a fix. I remember walking into the office waiting-room and seeing Gregory among my bewildered clients, head down, sweat rolling off his nose, suffering, junk-sick but very patient. I quickly slid him a twenty and, without a word, he was out the door. (152)

Such an image is important and moving: a remembrance of the criminal and humane aspects of the poet. But this image only finds its higher articulation—its place among a synchronous and impossible whole—in a later anecdote regarding the night Corso met Allen Ginsberg:

Gregory told me that, in his profound innocence, he asked Allen if he would like to watch a man and woman screw. Gregory told Allen that every day at the same time he watched a man and women have sex through an apartment window and would masturbate. Gregory suggested that Allen go with him and check it out and masturbate too. By some fantastic twist of fate, it was Allen and a woman screwing that Gregory had been watching! Allen was gay, of course, but he had been seeing a psychiatrist who advised that he could “be cured” of his homosexuality by having regular heterosexual intercourse. By the synchronicity that brought Gregory and Allen together, Gregory first knew Allen through the window. (153)

One inflection of this synchronicity has to do with the stated nature of the Beat Generation: a movement which Jay Jeff Jones called “a criminal enterprise in itself” (36). It can be easy to forget that a criminal element is always reflective of a larger system of order: the language and culture of the street are always dialects of the state: chaos is simply a different pronunciation of order. The Beats, and Corso no less, brought literary and bio-mythological representations of the material relationships between the part (the lint brushed off a lapel, the ashes of the soldier, the woman screaming in the asylum) and the whole (the epic hero, the whitewashed Whitman).

But this synchronicity transcends materiality, which may speak to our opening inquiry: why is Corso’s name not carried on the same lips that would invoke Ginsberg, Kerouac, or Burroughs? And, subsequently: why does a critical and elegiac work about Corso run up against the risk of banalities of historicity? I feel that Corso’s own poetry, sometimes highlighted in this collection, offers not an answer but at least a meditation in response:

Existence as seen & felt by godhead

manhead analogous to it—

i.e., each part reflects the whole

god mind the mirror-man mind the reflection

each mind is like a cell in god mind

each cell of man mind

The whole can never be given whole

part cannot give whole (238)

Arriving at the end of Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet means arriving at the conclusion that there is no clear image of Gregory Corso or his Beat Generation. Biographers can psychoanalyze, literary critics can enact their exegesis, and archivists can unearth new details of a man’s life… but the poet and his works cannot be crucified on a cross of any such design. Read this collection—enjoy it as old friends around a fire relate memories of the dead. At the end of things that is all for which we can ask.