Vanilla Cupcake was talking shit again, talking about how she would give anything to get in my bed for one hour. One hour is all it would take. It ain’t nothin’ nice bein’ the only African-American in a circus full of wack ass crackers. Sometimes I drop my g’s. Nothin’. Bein’. I’m from Killeen, Texas. Fuck y’all. But I’m educated. I know how to talk like the white man. I only drawl when I have to. The thing is, I’m not some ignorant asshole selling balloons and cotton candy. What I do takes talent and balls. I’m a circus clown. The circus is in my blood. My parents were trapeze artists. My mom ran off with a German tourist. She still sends me Christmas cards from Berlin. My dad drank himself to death. I tend to keep to my damn self. Only woman I ever gave a damn about was Sugar Delicious. Best trapeze artist since Lillian Leitzel. She wore the hell out of those sequins. But Hollywood snatched her up and now she’s married to some hot shit producer and they have five perfect kids and two or three houses. She was up for an Oscar a couple of years ago.

But Vanilla Cupcake is lookin’ better and better. Sleazy chick. Wears too much makeup even when the tents are down and we’re all just chillin’. I guess she thinks she’s got somethin’ to prove since she ain’t nothin’ but a concession stand chick. She overcompensates with the dirty talk and the drinking and the drugs. Wants the world to know that she’s as tough and sorry as any man.

“When you gonna let me have a taste of that lollipop?” Vanilla Cupcake slurred, leaning toward me at the card table and giving me an extra close view of her ample cleavage and a whiff of her cheap body spray.

“I ain’t got no lollipop,” I said, puffing on my Cohiba and studying my hand. I didn’t have shit. A ten of clubs, a five of diamonds, a two of spades, an ace of hearts and a king of clubs.

“Oh, since when? Did Sugar bite it off?”

“Don’t say shit about Sugar.”

“I’ll never be rich and famous. I’m so sorry. I’m just a circus peasant, same as you.”

“You ain’t nothin’ like me.”

“You think you’re too good for me?”

“Nah. It’s the other way around.”

“Aw, that’s the sweetest thing you’ve ever said to me, cookie wookie.”

“It’s too soon for terms of endearment. Look, go get me a Coca-Cola for my rum.” …

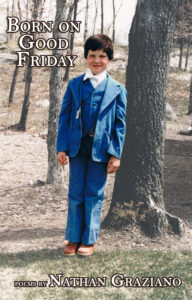

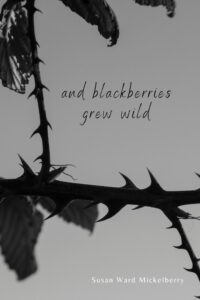

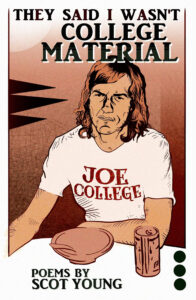

Read the rest in CLOWN GRAVY, short stories, by Misti Rainwater-Lites (Roadside Press) available at https://www.magicaljeep.com/product/gravy/147 or other online retailers.