Last Night I Sat Alone

Last night I sat alone waiting for you

on the ground in the sun under the oak,

as I had waited long ago.

The wind rustled the trees and the undergrowth.

I drew with a stick in the sand

what looked like a Mayan temple.

My white t-shirt reflected the last sun.

I waited, but you didn’t come.

A black dog came out of the woods

and caught me unaware. I waited,

but you were caught up in your living

and had forgotten me.

The wind blew over my shoulder.

Near me the raspberries grew.

Everything

Everything seems to be

moving toward me.

at a steady speed.

Until it gets close, and

then it slows down.

And then it comes right on in.

It doesn’t seem to be in my body.

Where did it go?

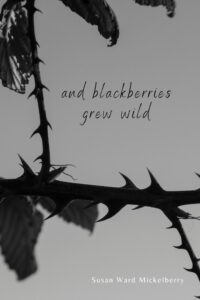

Susan Ward Mickelberry, born in Miami during WWII, has lived around the continental US and in Africa, where she spent several childhood years in Asmara, Eritrea, an event that colored her life. She earned an MA in English Literature from the University of Florida and lives with her cats in Gainesville where she worked as an editor and writer at UF. A lifelong student of ballet and dance, she teaches yoga and participates in regional poetry readings and events, including PoJam, the longest running open mic in Florida. Her poem “The Conversation” was Finalist in the Florida Poetry Contest at the Florida Review. Other poems appear in Blue Moon Review, Via I, Greensboro Review, Florida Quarterly, The Melrose Poetry Anthology, This is Poetry, Volume IV: Poets of the South, AC PAPA No. 3, and others.

Written over a lifetime, these lyrical poems reflect on childhood, early marriage, motherhood, and multiple long relationships in what proves to be rocky going. The author puzzles, attacks, muses, jokes, and meditates, seeking a way through ever-changing personal landscapes situated within the cultural tumult of late-twentieth-century America and more specifically in the strange beauty of north-central Florida. In several poems, she contemplates her nomadic youth as a military kid; born in Miami, she eventually lived in six states and spent two far-flung years in Asmara, Eritrea, Africa. The shadowy but powerful memories of those early years—hibiscus, clouds, elusive scents, radio tunes, flowering gardens and trees—permeate these musings by a poet trying to find some sense and intelligence somewhere in this always disappearing world, looking for grace, finding herself a little at a time. Influenced by authors as diverse as Mark Strand, Charles Bukowski, and the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, Susan Ward Mickelberry presents the outcomes in AND BLACKBERRIES GREW WILD.

Written over a lifetime, these lyrical poems reflect on childhood, early marriage, motherhood, and multiple long relationships in what proves to be rocky going. The author puzzles, attacks, muses, jokes, and meditates, seeking a way through ever-changing personal landscapes situated within the cultural tumult of late-twentieth-century America and more specifically in the strange beauty of north-central Florida. In several poems, she contemplates her nomadic youth as a military kid; born in Miami, she eventually lived in six states and spent two far-flung years in Asmara, Eritrea, Africa. The shadowy but powerful memories of those early years—hibiscus, clouds, elusive scents, radio tunes, flowering gardens and trees—permeate these musings by a poet trying to find some sense and intelligence somewhere in this always disappearing world, looking for grace, finding herself a little at a time. Influenced by authors as diverse as Mark Strand, Charles Bukowski, and the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, Susan Ward Mickelberry presents the outcomes in AND BLACKBERRIES GREW WILD.

purchase And Blackberries Grew Wild here >> https://www.magicaljeep.com/product/blackberries/155