First published at:

https://blues.gr/profiles/blogs/q-a-with-countercultural-writer-interviewer-and-editor-leon-horto

Interview by Michael Limnios

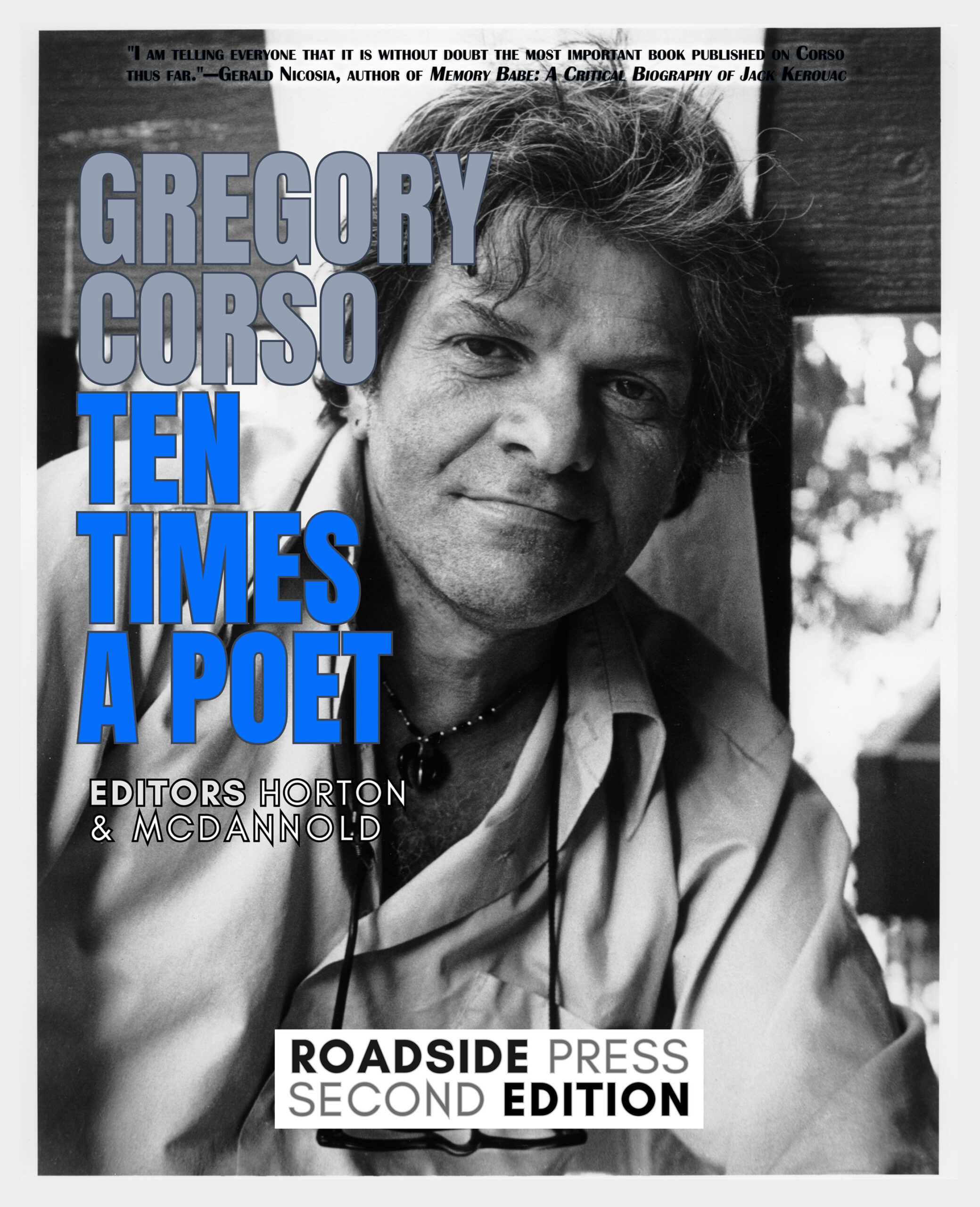

Q&A with countercultural writer, interviewer, and editor Leon Horton; editor of book Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet

“Where would we be without it? Literature helps us to understand the world, to see and feel and empathise with other cultural values, other points of view. It stimulates our thinking and, on a very basic level, entertains us.”

Leon Horton: Under the Counterculture

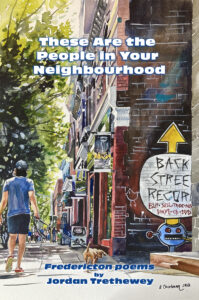

Leon Horton is a countercultural writer, interviewer, and editor. A regular contributor to International Times and Beatdom, his essays and interviews include “Hunter S. Thompson: Fear and Loathing in utero”; “Keeper of the Sacred Scrolls: An Interview with Bill Morgan”; “Charles Bukowski: Only Tough Guys Shit Themselves in Public”; and Gerald Nicosia: Jack Kerouac in the Bleak Inhuman Loneliness”. He is the editor of a forthcoming book Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet, a collection of essays, memoirs, poetry, photography, and artwork in celebration of the legendary Beat poet. His new book Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet (Roadside Press) will be available from Amazon in June 2024 or can be pre-ordered at magicaljeep.com.

(Photo: Leon Horton, a countercultural writer, interviewer, and editor)

He has written several feature articles on Beat-related subjects, most recently a piece on the English artist Jeff Nuttall for Beat Scene Magazine. Leon says: “For me, it all started when a friend lent me a copy of Naked Lunch, sometime back in 1991/92. I’d never even heard of William Burroughs or the Beat Generation at that time. I read Naked Lunch in one sitting, coming down from an acid trip, and I couldn’t put it down. I couldn’t believe what I was reading, let alone that it was written and published in the late 1950s / early 60s. I haven’t looked at the world in the same way since.”

How has underground literature and the counterculture influenced your views of the world?

For me, it all started when a friend lent me a copy of Naked Lunch, sometime back in 1991/92. I’d never even heard of William Burroughs or the Beat Generation at that time. I read Naked Lunch in one sitting, coming down from an acid trip, and I couldn’t put it down. I couldn’t believe what I was reading, let alone that it was written and published in the late 1950s / early 60s. I haven’t looked at the world in the same way since.

How did the idea for Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet come about?

It was on a trip to Athens. I was standing on the Acropolis, staring out across the city, lost in some sort of spiritual moment, when it dawned on me that I was standing where Gregory himself once stood. I determined there and then I was going to write something about his adventures in Greece. That essay, which is included in Ten Times a Poet, was subsequently published in the literary journal Beatdom in 2022. Shortly after, I made a throwaway comment on Twitter to a publisher about doing a Chapbook in celebration of Corso. The publisher (who shall remain nameless) was very keen but turned out to be a complete crook and the whole thing collapsed. Thankfully, Michele McDannold at Roadside Press was interested and wanted to develop the project into a full-length book. It’s down to her hard work, diligence, and patience with me that the book is going to be published. It’s taken a long time, with more and more brilliant writers, photographers, and artists coming on board – Anne Waldman, Ed Sanders, Neeli Cherkovski to name but three – and I think the result is a testament to Corso’s legacy.

What was it about Gregory’s life and work that touched you?

It’s curious, but I was quite dismissive of Gregory when I first read about him in the biographies of the other Beats or saw him in documentaries. I thought he was just a bitter hangover. It wasn’t until I started to read his poetry and learn about the trauma he faced in childhood and beyond that I realized what a remarkable survivor, what an incredible poet he was; capable of great humour and beautiful insight into the human condition.

He could be a nightmare to deal with, I know, but the outpouring of love for Gregory in Ten Times a Poet from those who knew, worked and lived with him just astounded me. Allen Ginsberg said Gregory was a better poet than himself. He was damn right.

Why do you think the Beat Generation continues to generate such a devoted following?

Well, we all love a rebel, don’t we? On some fundamental level, we need voices of dissent – especially in these shit-storm days we are currently living through. I don’t know; this is actually a difficult question to answer. I guess much of what the Beats said and did and wrote about in their time remains as pertinent, as true today, as it was back then – that need and willingness to cry out, “No, I won’t do as you say, go fuck yourself!”

How important is music to you? Does music affect your mood and inspiration?

Music has been hugely important throughout my entire life. My mother was (and still is) a huge fan of The Rolling Stones – I was listening to them in the womb. Growing up, I got to hear mum’s favourites: Rock ’N’ Roll, Motown, Soul, Blues… When I moved to Manchester in the late 1980s, I became friends with a lot of people, many of them musicians, who introduced me to so many different kinds of music and just opened up my world.

Does music affect my mood and inspiration? Even though I know nothing about it, I sometimes have jazz playing on the radio when I’m working. There’s something in those (wordless) beats and rhythms that I find conducive to writing.

What has been the most interesting period in your life?

Well, moving to Manchester in 1989 was precipitous – just in time to experience the so-called “Madchester” scene. It was like an explosion, with the legendary Factory Records and bands such as The Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses, and – my all time personal favourite – The Fall. There was no other band like The Fall. And two or three times a week we’d be popping pills and dancing our nuts off in the Hacienda. For a while there, albeit briefly, the Hacienda was the most famous nightclub on the planet and Manchester seemed like the centre of the universe. I didn’t see it at the time, of course, but when I think about it now I realise we were living through cultural history.

“Well, we all love a rebel, don’t we? On some fundamental level, we need voices of dissent – especially in these shit-storm days we are currently living through. I don’t know; this is actually a difficult question to answer. I guess much of what the Beats said and did and wrote about in their time remains as pertinent, as true today, as it was back then – that need and willingness to cry out, “No, I won’t do as you say, go fuck yourself!”” (Photo: Leon Horton, editor of book Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet)

Do you have a dream project you’d most like to accomplish?

Oh, yes. I’m working on a book about the 1965 International Poetry Incarnation that took place at the Royal Albert Hall. Seventeen poets performed that night, including Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Gregory Corso – but it was more than just a “Beats in Britain” thing. It was the event that is widely regarded as kick-starting the whole countercultural scene in the UK. Just before he passed away in 2023, I was lucky enough to interview poet and musician Pete Brown, who performed that night. Pete, as I’m sure you know, started out as a jazz poet and went on to write the lyrics for Cream’s “I Feel Free” and “White Room”. He was a remarkable man and a brilliant raconteur.

What socio-cultural impact does literature have today?

Where would we be without it? Literature helps us to understand the world, to see and feel and empathise with other cultural values, other points of view. It stimulates our thinking and, on a very basic level, entertains us. The mediums and the modes have changed with the rise of social media and other platforms – but that isn’t always a bad thing. I tend to look at it as similar to the mimeograph revolution and all the “little magazines” of the 1950s / 60s that helped democratise literature and give new writing a voice.

Let’s take a trip in a time machine. Where and when would you like to go? And what memorabilia / music would you take with you?

Oh, that’s easy. I’d go back to five minutes before Elton John’s parents were about to get down to it, with a copy of his greatest hits, and I’d say, “Oi! You two! No!” And then I’d play them the album and show them what the future will be if they don’t just stop what they’re doing.

What meetings / interviews have been the most important to you? Are there any memories you’d like to share?

Writing for International Times and Beatdom, I’ve had the honour and great fortune to interview some important names in Beat studies: Bill Morgan (author of The Typewriter is Holy and I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg), Gerald Nicosia (author of the superb Kerouac biography Memory Babe).

The one that stands out for me, however, was an interview with Victor Bockris for his forthcoming book, The Burroughs-Warhol Connection. Victor is an interviewer’s wet dream. The stories he told me, of the incredible artists he has either interviewed or written about – William Burroughs, Patti Smith, Keith Richards, Lou Reed, Debbie Harry… Pure gold! The dinner party he threw for Burroughs, Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol was nothing short of a disaster. I was crying with laughter when he told me about it.